A colleague writes to you for advice:

Can we have a call, as I’d like to know how to do some product management stuff?

And you think — “wow … what a topic”. Where to start? Though you’re a helpful person, you’re busy and you’d need more info.

Imagine that the same person writes this to you instead:

I’m being promoted to more of a leadership role where I help to shape our services for the rest of the business. But the groups I have to work with aren’t very clear where they’re going. There’s a dev group that is quite motivated but they seem to promise things that take longer and longer. There’s a product owner who’s supposed to be more on the business side but spends more time with the dev team. The main business stakeholder has recently changed and instead of focusing on the software is now saying we just need more customers. I actually feel we’re on borrowed time now. I feel that product management frameworks could help. What do you suggest?

Now, you have something to go on.

You might have a lot of questions. You might question the focus on software as opposed to value. If you know some of the people, you might suspect there is more to the story. But, you’re engaged, and you want to help.

It was easy for you to see the gaps in the first message, and the improvement in the second, because you’re in the position of the reciever. But do you always write enough context into your own messages? It’s hard. The “curse of knowledge” makes it hard to imagine being someone who doesn’t know what you know.

What is the Curse of Knowledge? Don’t worry — it’s not a curse as in “mysterious ill-fortune after opening a pyramid”. Even though the caret symbol does look a bit like a pyramid. Hmmm.

The Curse of Knowledge is the phenomenon that when you know about something, it’s hard to get back in the mindset of those who don’t know the thing. So it’s hard to communicate the thing to them without getting into confusing detail.

Dan and Chip Heath explained it neatly in “Made to Stick”:

Lots of us have expertise in particular areas. Becoming an expert in something means that we become more and more fascinated by nuance and complexity. That’s when the curse of knowledge kicks in, and we start to forget what it’s like not to know what we know.

The phrase was originally coined by Colin Camerer, George Loewenstein, and Martin Weber in their paper “The Curse of Knowledge in Economic Settings”. I also like their more precise description of this phenomenon:

In economic analyses of asymmetric information, better-informed agents are assumed capable of reproducing the judgments of less-informed agents. We discuss a systematic violation of this assumption that we call the “curse of knowledge.” Better-informed agents are unable to ignore private information even when it is in their interest to do so; more information is not always better.

What was different with the version # message? It depicted a scenario. A scene. There were characters, and tension. There was a context. It could draw you in and make you want to help.

You might say, “oh, so it’s storytelling”. But it’s not exactly. There is no once-upon-a-time; no beginning, middle, and end; no need to imagine the hard facts of your business animated in Pixar-cuteness.

An honest picture of a situation gives people agency. You can of course suggest resolutions. But tidy stories may not help. For more, see “Strategic thinking isn’t storytelling”.

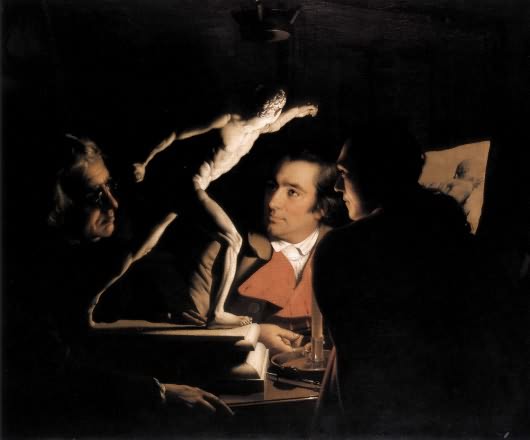

What else highlights characters and tension with context, without being a complete narrative? A dramatic painting. And what genre paintings could be more dramatic than those which show gritty myths and religious stories with new tools of realism? I’m talking about the Baroque painters such as Caravaggio, Rembrant, and Poussin.

Perhaps this painting feels over-the-top, the style and its theme. For a moment, don’t judge. Just look at the spilling wine in the hands of the woman on the right.

Look at the gaze of the man on the left. At the king, interrupted in his feast. At the hand writing on the wall.

These depict a dramatic moment, some revelation. And you get a feeling of the situation, even if you don’t know the bible story behind it.

The Baroque paintings like this have three elements: a context (location and situation), some people, and a point of dramatic tension or action. Here, the context is the feast, the people are the king and his courtiers, and the dramatic tension is the writing on the wall.

You can use these three elements to describe a situation clearly at work. Here’s how:

- Context (just enough). Your reader needs to know something about the situation you’re writing from. If a team’s facing a challenge, where are the requirements coming from and what has been tried before?

Don’t give too much context though. Avoid a complete history; just outline enough detail that the reader can locate where their help is needed. - People. The main characters. Here, make sure to give enough detail. Not about physical characteristics, of course, but about the roles that people play (related to the topic of your message), and what drives each person or team. If I’m meeting some new people I take time to read about their work experiences and any particular interests. It makes for better conversations. The same is true for writing about situations.

- Dramatic tension or action. What is your main question or concern! Paint it bold. Use it at the start of your message, to draw your reader’s attention to what’s needed. Put it at the end as well, to spur action. Many of the Baroque painters used light and shadow to highlight the action and key characters.

Baroque techniques of shadow and light

Chiaroscuro refers to the way that shadow is used to offset the lighter areas in a painting or photograph. The technique became popular in the Baroque era, though has been used since then too, by artists such as Gerome, Goya, and even modern comic artists (here’s a great example: https://yanickpaquette.substack.com/p/chiaroscuro)

Chiaroscuro is an umbrella term for the contrast of light and shadow. When the contrast is more pronounced, this can be called “tenebrism”.

Here are two more examples of these three elements. Firstly, another religious subject, a painting my family and I saw last year:

The context is the Biblical location of the pool at Bethesda; you can see it in the background. But try narrowing your eyes until you see only the bright areas of the painting. They are Jesus and the paralysed man (and the angel in the sky). So the focus is on these people. The action? Look at the upwards gestures of Jesus and the paralysed man, and the upwards movement of the man’s body. He’s being raised up — the miracle in action.

But the Baroque painters didn’t only show religious or mythical subjects. Science was progressing fast. Here’s Joseph Wright’s “The Orrery” from 1766.

Here, the context is shown subtly — the books behind the curtain showing that this is some place of study, a library or laboratory.

The people are not only the scientist and other adults but the children. In fact, the brighest things in the painting are two of the children’s faces.

The action is the demonstration of the workings of the solar system — an inspiring thing particularly for the children, who might continue exploring the world and its workings in later life.

Still not sure how how to start using this approach with things you write at work? Try it backwards.

Next time you have something a little tricky to communicate, a situation to depict, think first about what you want to highlight: the key tension, decision, or needed action.

And then work backwards to fill in the helpful information about the people involved, and the context — the history and wider organizational background.

Why not try an exercise now. Think about a situation at work that you’d like to communicate to a boss, a colleague, or a team. Now see if any of these great chiaroscuro paintings echo the emotions, risks, or opportunities of that situation in any way!

Leave a comment